|

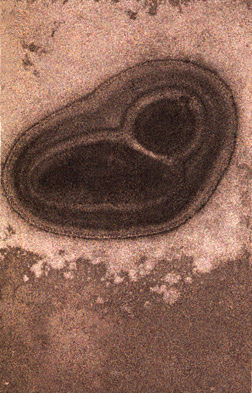

| Turnbull, numerical structure 2, 2012 |

The Hosmer Gallery is located at the

Forbes Library in Northampton, Massachusetts, about a 2-hour drive west from Boston. Very soon you'll be able to see some of

Richard Turnbull's work from 2010-2012 there, in a much anticipated show running February 1 to February 28, 2013. Am I giving it all away by saying that my favorite is the surprising, apocalyptic 'glyph studies 1'?

|

| Turnbull, glyph studies 1, 2012 |

Meanwhile, down in Pennsylvania

Norm Sarachek is having a show at

Santa Bannon Fine Art in Bethlehem from December 7 to December 30, 2012, featuring his new 'Steel Works' series.

|

| Sarachek, Steel Works 1, 2012 |

|

| Sarachek, Steel Works 2, 2012 |

He follows that up with another show at the

Perkins Center for the Arts in southern New Jersey which runs from February 9 to March 23, 2013, because you'll need to see more of this fine artist.

The inventor of the so-called chromoskedasic variation in chemigrams,

Dominic Man-Kit Lam, recently concluded a huge show with over 100 works at the

Shanghai Art Museum (China) this past October 2012 entitled 'Vision of Harmony'. He also spoke at the event, and an

inspirational video of it has been posted on YouTube.

|

| Man-Kit Lam, from Vision of Harmony, 2012 |

|

| Man-Kit Lam, from Vision of Harmony, 2012 |

|

| Man-Kit Lam, installation view, Vision of Harmony, 2012 |

Back in New York,

Eva Nikolova is exhibiting chemigrams from her new series 'Ordinary Disappearances', which offer imaginary but quite emotional Balkan landscapes from and about memory, triggered by a trip to her homeland after many years' absence. The show is at the Grady Alexis Gallery in

El Taller Latinoamericano in upper Manhattan and runs from November 26, 2012 to January 9, 2013.

|

| Nikolova, untitled IV, 2012 |

|

| Nikolova, untitled VI, 2012 |

A blog regular,

Nolan Preece, is presenting both chemigrams and glassprints at the

PUB Gallery, Wildflower Village, Reno, Nevada from November 29, 2012 to January 15, 2013.

Chemigramist

Douglas Collins exhibited in the recent Alternative Processes Competition at

Soho Photo in lower Manhattan from November 7 to December 1, 2012. He will also be in the annual group show at the

Center for Photographic Art in Carmel, California, from January 12 to March 1, 2013.

.jpg)