|

| Schulz, Vase with flowers after Daniel Seghers, before 1637, 4/9, 2014-2016 |

There are different ways to get into the work of Joachim Schulz, some easy, some more demanding. I took the easy route, poking through lush masses of flowers. Who is heartless enough to resist that? In my carefree summer mood the other day I didn't have a thought in the world for the past or future of photography and I was happy leaving its deconstruction to others. Today what I wanted was fragrance, vibrancy, a delicacy of depth, a fervent softness. By the merest chance some pictures by Schulz, then unknown to me, fell into my lap, the one above being one of them, and yes, that was it - I literally stopped breathing, I was gone.

But with Schulz there is always a backstory, as I was to learn. There is an object lesson, as if his pictures were moral tales, and often a tipping of the hat to another tradition, old or recent, or to a trail of perception almost lost because it had no champions to claim it until now, until Schulz came along. 'I do photography in a narrow sense,' he says. More about that in a minute - back to the flowers.

Here's what I know: he photographed, or scanned or downloaded, paintings of flowers by Flemish masters of the 17th century, which was the great period of the cartouche, the bouquet, and the garland, when wealthy burghers regarded no home complete without a painting abrim with flowers. In Antwerp, Ghent, Utrecht and Brussels the production of such works employed hundreds of artists, if not thousands - it was on an industrial scale - not to speak of gardeners because without them you'd be nowhere. While this was the time of Rubens and Breughel, most of the artists chosen by Schulz dedicated themselves exclusively to floral compositions and are not widely known today beyond a small circle of specialists and fans: de Fromantiou, Byss, de Heem. But all were excellent with brush and pigment.

Next Schulz printed out the images, but not in the usual way. He seems to have purposely jimmied the print nozzle, or perhaps he overrode the controller of the print mechanism - I haven't spoken with the artist so I'm inferring a lot here - to allow abnormal splurges of ink to be discharged onto the print media, whether paper or acetate. Some of you readers may have experienced the same thing but as a problem rather than a gift, when you had a mismatch of ink and media in your inkjet. With Schulz, this surplus ink would pool and flow randomly, to create distorted forms in some areas while leaving other areas basically intact. He didn't rest with this though but continued on, scanning the result back into his computer and printing it out again, again with the amplified print nozzle, to obtain a variation on the first print. He repeated these steps nine times, generating what printmakers call a 'variable edition' of nine. Alternatively you could call each print 'unique', which is what the Von Lintel Gallery of Los Angeles does in their current show of his work, Blumenstilleben, or Flower Still Lifes. The prints there are presented as archival digital prints and measure 50 x 35 cm each.

To illustrate the changes a single image undergoes with this method, below are the first four prints (out of nine) Schulz made from a picture that Jacob van Hulsdonck painted back in 1608. The evolution of the piece is fascinating; in its swerves and readjustments it recalls textbook diagrams of the development of an embryo, or of a city. The concept of time is bound up within it.

|

| Schulz, Flowers in a glass vase after Jacob van Hulsdonck, after 1608, 1/9, 2014-16 |

|

| Schulz, Flowers in a glass vase after Jacob van Hulsdonck, after 1608, 2/9, 2014-16 |

|

| Schulz, Flowers in a glass vase after Jacob van Hulsdonck, after 1608, 3/9, 2014-16 |

|

| Schulz, Flowers in a glass vase after Jacob van Hulsdonck, after 1608, 4/9, 2014-16 |

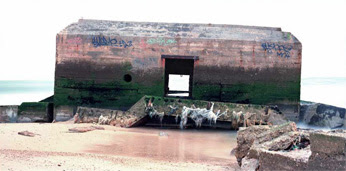

Schulz brings to the task an incisive sense of modern themes and issues, from the seriality of the variable editions to his repetitive, almost industrialized method of production, in passing by the use of appropriation - taking earlier art and reworking it - a strategy as old as art itself but which in the right hands can still seem fresh and impudent. He is foremost an experimentalist, and his work raises questions about what it is that we're looking at when we look at a photograph: are we the subjects after all, in the end, as we try to build an image from what the world has given us? His earlier work could be viewed as a fairly odd set of photographic queries or conundrums that circle this, without ever arriving: from studies of the faint light emanating from the stage curtains of old movie houses to an essay on the patina coating decaying German bunkers as they slip into the sea.

|

| Schulz, o.T. #3, framed behind glass, 72.5 x145.2 x 4.8 cm, 1999-2001 |

As to his flower still lifes, with their quirky shapes drifting lazily off the edge of the paper, their riotous color, it all makes for a highly engaging experience, rivaling what Bobby Bashir is doing more naively out in central California, and so unexpected too when considering his past efforts which make for somewhat dry viewing, truth be told. But these flowers! I wish he would tell me that it's OK to love them.