|

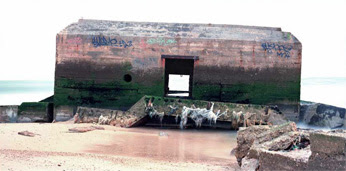

| Naticchioni-Rojas, Skins series, 2015 |

|

| Naticchioni-Rojas, Skins series, 2015 |

Three years ago, in her Milan studio, Cinzia Naticchioni Rojas was working with photographic prints on ceramic tiles. She had a problem - the images started detaching and floating off their support into the water. 'It was beautiful', she says, as she observed the images floating away. She was impressed with the tough material nature of analog images, whose substance, she felt, is really the silver gelatin itself and not the paper it is bound to, a distinction often misunderstood. 'I realized suddenly that the image floating was the true and unique essence of photography. Obviously it messed up my tile work, but for me it was like an epiphany.'

Her head now a jumble of new ideas, she switched away from ceramics and embarked on a careful course of research to see how she could develop this insight. Accustomed as she was to various substrates in her photographic image-making, she continued along these lines, using the black & white liquid emulsion by Rollei (similar products are available from Rockland Colloid and from Foma). She would apply the emulsion, let it dry, put it under the enlarger, and expose images onto it of her favorite subject, clouds (Cinzia's in love with clouds, maybe it's something about their stately movement, the way their slightest displacement seems thrilling - or then maybe not, we'll have to ask her). In any event, by early 2015 she had figured out a way to peel off the emulsion, intact, from the substrate, but then what? Where to go with it?

An architect by training, Cinzia tends to think in three dimensions. She looks down at the globs of wet emulsion before her and sees a potential for creating space, for this is what architects do. Dry it, make it rigid, stand it up, wrap things in it. Call them 'skins'. She could set the emulsion free, free to dance, fall, slump, or rest nonchalantly, the way the rest of us do at our most unmindful, waiting for time to unfold. She found the emulsion had a mind of its own; she accepted this. The best part was that it was autonomous and that it seemed to revel in its own surprising existence, if we can anthropomorphize it without going too far. Representation at this stage now becomes something quite arbitrary, something we didn't need, an appurtenance, even a hindrance, something quaint and beside the point. A faint trace of her beloved clouds does remain if you look hard, staining the crumpled emulsion, roiled and tarnished and eviscerated. But no matter.

|

| Naticchioni-Rojas, Skins series, 2015 |

|

| Naticchioni-Rojas, Skins series, 2015 |

And what a great distance the sky has come, from heaven's abode to the mud of the darkroom. We watch her skin-objects with fascination and awe; they are like skin-castles that we want to approach and inhabit, we want to live in them, never mind where they came from. From this moment we feel she is holding out to us something of a life without obligation, without ties and complications, like a gambol in the woods in the company of shadows.

It is on such occasions that she appears to close in on the rich tradition of cameraless photography, while advancing on it from a unique and undeveloped direction: instead of carving into the emulsion, she lets it fly, instead of creating images from gelatin and silver salts she builds structures out of them. Happily for us, she is not 'taking a picture' any more than a chemigramist or a bleach-etcher does, though some might argue, against popular sentiment, that this is the purest form of photography because is doesn't pretend in the least to represent: it is self-reflexive, it limits itself to ponder and wonder and celebrate the physicality of its own materials. We will not yet speak of beauty.

|

| Naticchioni-Rojas, Skins series, 2015 |

Her work is now at a crossroads between so-called photography and real photography and it's too early to tell what she will do next (she may do all of it). The 'skins' series has given us good reasons to be tantalized.

O

O