|

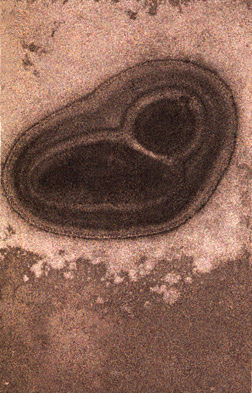

| Cordier, 21/4/72 I after a computer drawing of Manfred Mohr, 1972 |

The

Haines Gallery of San Francisco has mounted a geometry-flavored show entitled "Poetics of Construction" featuring

Pierre Cordier, Ai Weiwei, Andy Goldsworthy, and the amazing Monir Farmanfarmaian, among others. The objects in this show - and most are indeed objects, with a sculptural physicality evident or implicit - have a brooding presence and seem to rest comfortably, even authoritatively, in their appointed space. Cordier's chemigrams from 1972 fit in nicely with this concept. Back then, he had just begun to collaborate with Manfred Mohr, the computer art pioneer, who was fresh from exhibiting his first computer-plotted drawings at the Museum of Modern Art in Paris. For Cordier, this was to mark the beginning of a 20-year preoccupation with grids, graphs, and glyphs in some of their more austere forms, mollified perhaps by the chemigramic filter; only since the millenium has the hold of this spell on him begun to ease. The works shown at the Haines reflect the early stages of that collaboration.

|

| Cordier, 22/4/72 I after a computer drawing of Manfred Mohr, 1972 |

The titles refer to the dates of execution and are written in Romance-language style with day, month, year in that order. So that these two pictures were done on Friday and Saturday, the 21st and 22nd of April 1972. Why are these dates interesting?

On that very Friday, while Cordier was bent over his darkroom trays, the Apollo 16 spaceship landed on the moon, in an unexplored region called the Descartes Highlands. Astronauts climbed out, stumbled around in that strange gravity, collected rock samples, took snapshots of each other, saluted the earth and climbed back in. Cordier was just finishing the first picture. The following day - Saturday - one of the largest housing projects in America was intentionally demolished by the government because the tenants refused to live in it any longer: they had said they were treated like rats and it was intolerable. That was Pruitt Igoe, in St Louis, and the documenting of its demolition, which was unprecedented, became one of the iconic moments in the film

Koyaanisqatsi (Life Out Of Joint, in the Hopi language) by Godfrey Reggio and Philip Glass. Cordier meanwhile was just completing the second. In the brief space of a day, a monstrous tension between life as it is and life as it might have to be, or become. In my mind this tension drifts over and envelopes Cordier in his studio, he unaware yet somehow understanding. His marks are faint but made with a firm and serene hand, his voice no more than a whisper, I see his lips barely moving. He has been given to record the allegory. I exagerate but then I do not.

|

| Apollo 16, Moon, near the Descartes Crater, 1972 |

|

| Pruitt Igoe, St Louis, 1972 |

The Cordier works on display are c-prints from the chemigram original, printed in editions of 12. The show runs until March 9, 2013.