|

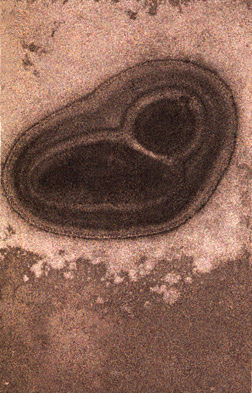

| fig. 1 Charcoal R |

To a darkroom maven, there's nothing like discovering a paper you've never used before and which, as sort of a gift from the photographic gods, displays qualities both unexpected and lovely. One such for us recently has been Luminos, particularly the Charcoal R and the Tapestry X. It began when my friend Lou Spitalnick let us have some of his old stock from the house he keeps at the end of Long Island. "Go ahead, take what you want," he said. Was his smile a knowing one?

We did. Rich Turnbull was first to have at it and created the Charcoal R images in figures 1 and 2. It turns out it's a warm-tone, fiber-base paper, probably a chlorobromide emulsion, but that's not what stands out. First, it's the texture. Charcoal R has a rough texture, rather similar to certain varieties of printmaking paper. You pass your fingers over it and they tingle: the surface speaks. But the paper's architecture has another secret, and that is that the emulsion seems to be buried deep within it, not at the surface. Did the Luminos people plan on an unsized, highly absorbent paper, like a waterleaf paper? That seems to be the case, because the images you get from it have a hazy, muted cast, as if they were peeking out shyly from a forest of paper fibers. In the case of colors, this produces a whole range of tones and qualities new to our experience.

|

| fig. 2 Charcoal R |

|

| fig. 3 Tapestry X |

Tapestry X has the same formulation, with the difference that the paper has been given a more pronounced, canvas-like feel, an artsy effect popular in the years after WWII - witness now forgotten names like Wellington Art Canvas, Velour Black, Athena Old Master, etc. Note the grain of the texture. The problem with using this paper for chemigrams however is this, that it's so unsized your varnish resist just sinks in and apparently cannot form a tight varnish-emulsion bond, essential for the elaboration of incisions and mackie lines. Its beauty is its curse. One solution is to apply multiple coats of varnish, letting each dry in turn, so that you build up a scaffold of varnish material to work with. Without this the varnish won't adhere to the emulsion; you'll get scumbling and lifeless incisions, as seen in figure 4. (Some may actually favor this, of course!)

|

| fig. 4 Tapestry X |

Luminos production began in 1947 and was discontinued in 2005, probably under the onslaught of the 'digital revolution' although their press releases at the time spoke of paper supply issues. Luckily, the papers are still available online. Or, if you have more time than we have, you can make your own, mixing potassium and silver salts with gelatin and a paper of your choice, with details on the internet.